Civic Education

Civic education empowers members of our network to participate fully in democracy and advocate for pro-voter policies. Civic education is essential for increasing voter turnout, expanding voter access, and helping people become year-round citizens.

Our civic education programs aim to give our network the tools they need to address the issues that matter most in their communities, including:

-

In many states, voter suppression laws pose significant barriers to voting, especially for minorities and low-income Americans.

For the most part, suppression laws are predicated on the phantom threat of voter fraud. There is no credible evidence to suggest that fraud takes place on a large scale: In fact, voter fraud or voter impersonation is about as unlikely to occur “as being struck by lightning,” according to a Brennan Center for Justice report, which found incident rates of voter fraud between 0.0003 percent and 0.0025 percent. Another study by the Washington Post cited 31 credible instances of impersonation fraud from 2000 to 2014, out of more than 1 billion ballots cast.

After the 2010 election, state lawmakers nationwide introduced hundreds of bills with harsh measures making it harder to vote, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. The new laws range from strict photo ID requirements and early voting cutbacks to registration restrictions, as well as limiting college student voting where they attend school, among other measures. Strict photo ID regulations threaten to disenfranchise many black and Hispanic voters who do not own a car or have a passport, and minorities and the poor disproportionately use early voting opportunities.

Overall, 23 states have new restrictions in effect since then — 10 states have more restrictive voter ID laws in place (and six states have strict photo ID requirements), seven have laws making it harder for citizens to register, six cut back on early voting days and hours, and three made it harder to restore voting rights for people with past criminal convictions. In 2016, 14 states had new voting restrictions in place for the first time in a presidential election.

In 2017, legislatures in Arkansas and in North Dakota passed voter ID bills, which governors in each state signed, and Missouri implemented a restrictive law that was passed by ballot initiative in 2016. Georgia, Iowa, Indiana, and New Hampshire have also enacted more restrictions this year, in addition to laws that were on the books for previous elections. Suppression laws are being challenged in the courts. These include the Ohio law that purges registered voters who do not vote over a two-year period.

In a victory for voting rights, the Supreme Court last year refused to review a lower court decision striking down a North Carolina law that slashed early voting times, eliminated same-day registration and killed preregistration for teenagers, among other measures. The appeals court had ruled that the law was intentionally designed to discriminate against black voters: North Carolina legislators had requested data on voting patterns by race and, with that data in hand, drafted a law that would "target African-Americans with almost surgical precision," the court said.

-

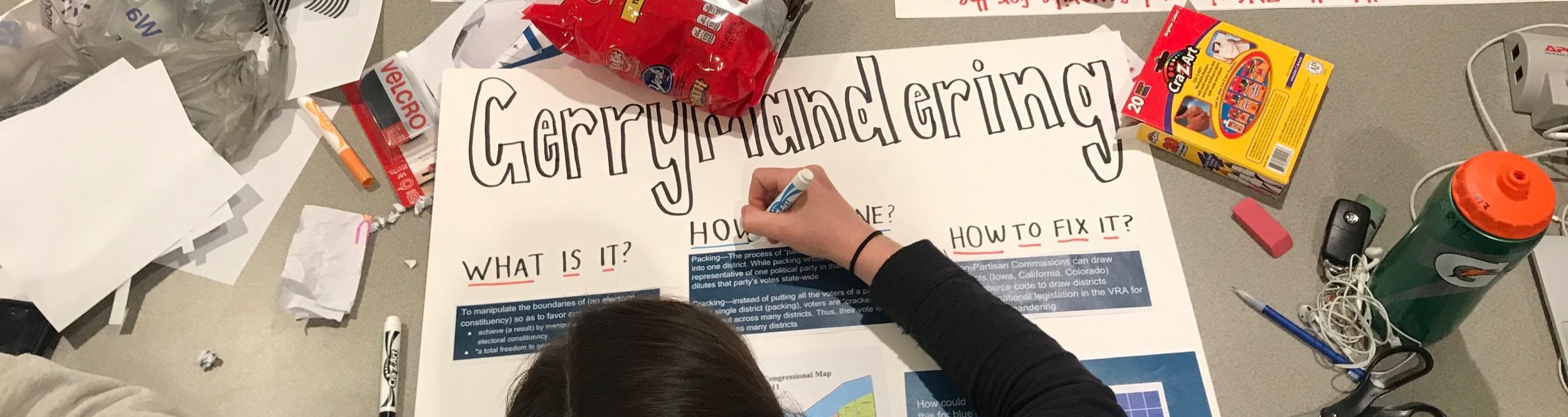

Gerrymandering refers to the drawing of state legislative districts to account for demographic changes and ensure that legislative maps accurately reflect diverse communities.

But partisan gerrymandering by both parties has become commonplace. It is a form of political manipulation in which politicians—often working behind closed doors—draw maps in favor of one party or the other. Essentially, the parties “pick” the voters who support them to maximize their advantage, rather than voters picking their political leaders. This process “locks in” the party advantage for at least another 10 years, when the maps are redrawn.

Gerrymandering results in distorted election results and effective minority rule—not to mention some extremely odd shaped electoral districts, such as the 7th in Pennsylvania, which is so contorted that it has been nicknamed “Goofy Kicking Donald Duck."

Egregious gerrymandering took place when legislative maps were redrawn after the 2010 census and the subsequent Republican landslide in midterms the following year. Afterwards, the Republican-controlled legislature in Pennsylvania drew a map that has limited Democrats to five of 18 House seats, although statewide elections tend to split evenly between the parties. Another example: In the Wisconsin state assembly election in 2014, Republicans who drew the map won 63 of the 99 seats with only 52 percent of the two-party statewide vote. In six states where Democrats drew the lines, their candidates won 56 percent of the vote but 71 percent of the seats.

Another downside to gerrymandering: Politically biased maps that cut across party lines can reduce the number of competitive races, and in turn that could dull voter interest. As a result, many disgruntled citizens who are fed up with the process and their lack of equal representation choose not to vote.

Increasingly, the courts are starting to address partisan gerrymandering. Recent decisions in North Carolina and Pennsylvania have struck down Republican-led redistricting. And the Supreme Court—which for years had been unwilling to tackle the issue—is taking up two cases: One in Wisconsin, where Democrats are challenging the Republican-drawn map used to elect the state assembly; and a second in Maryland, which concerns a Democrat-drawn congressional district in Maryland.

-

Long lines and waiting times at polling places are the new normal for many Americans eager to vote.

The lack of standardized structures, laws, and regulations across state-controlled voting systems—as well as antiquated voting machines and technology, lack of staff at polling places, and limitations imposed by voter suppression laws—have made registering and voting onerous tasks for many.

Many of these laws are draconian. Ohio, for example, cut an entire week from early voting. Arizona made it a felony to collect and turn in someone else’s ballot, even with the voter’s permission. Texas requires anyone wishing to collect voter registration forms to be an eligible voter deputized by the state registrar. Southern states have closed nearly 900 polling places since the Supreme Court struck down part of the Voting Rights Act in 2013.

These legal and statutory barriers are just part of the problem. In many states, the voting system has yet to experience the transformation that technology has brought to many other aspects of American society. Just 37 states and the District of Columbia allow online voter registration, and many states still rely on hand-written forms and hard files to keep track of voter information. Such antiquated practices leave the door open for large-scale voter purges and mistakes in record-keeping, both of which lead to disenfranchisement.

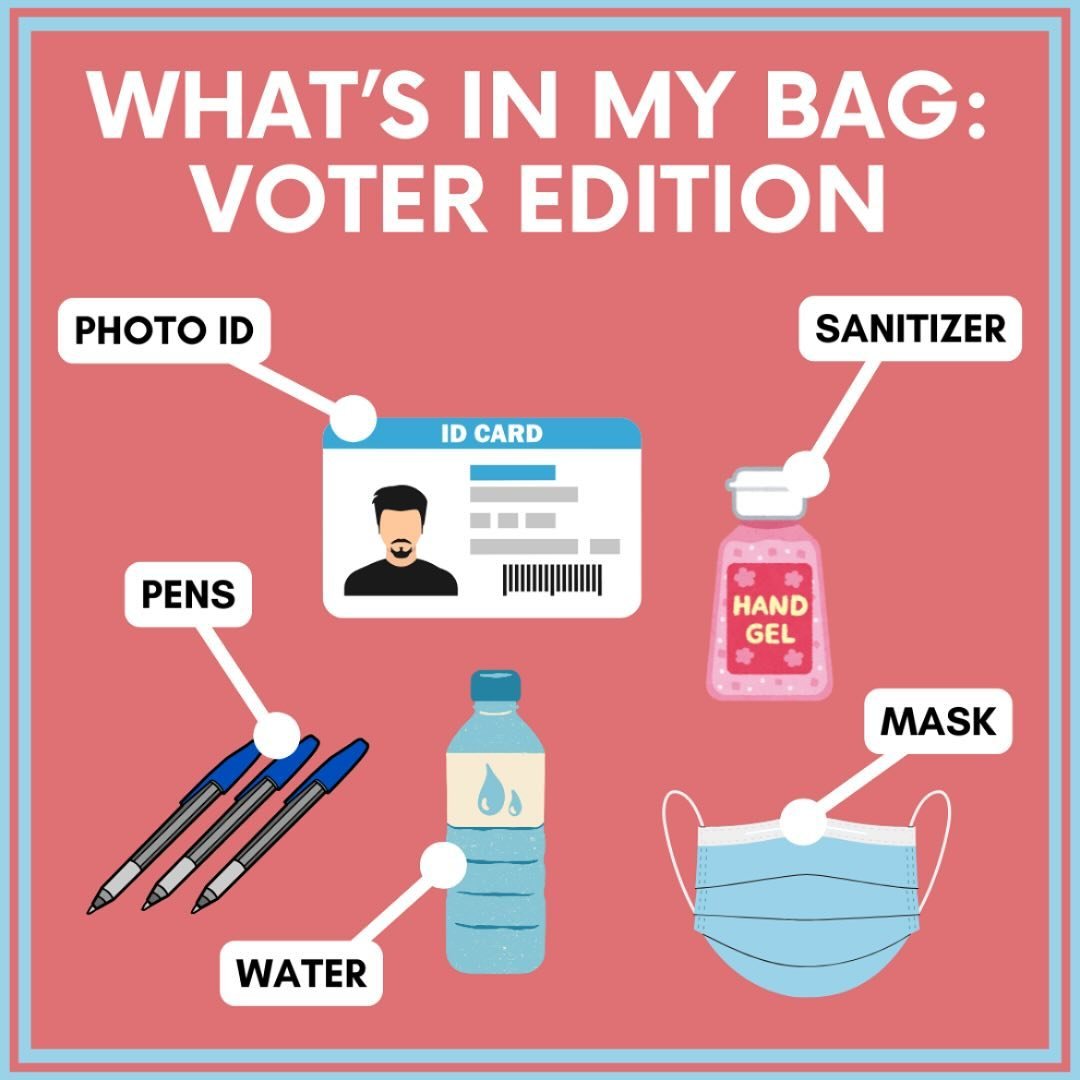

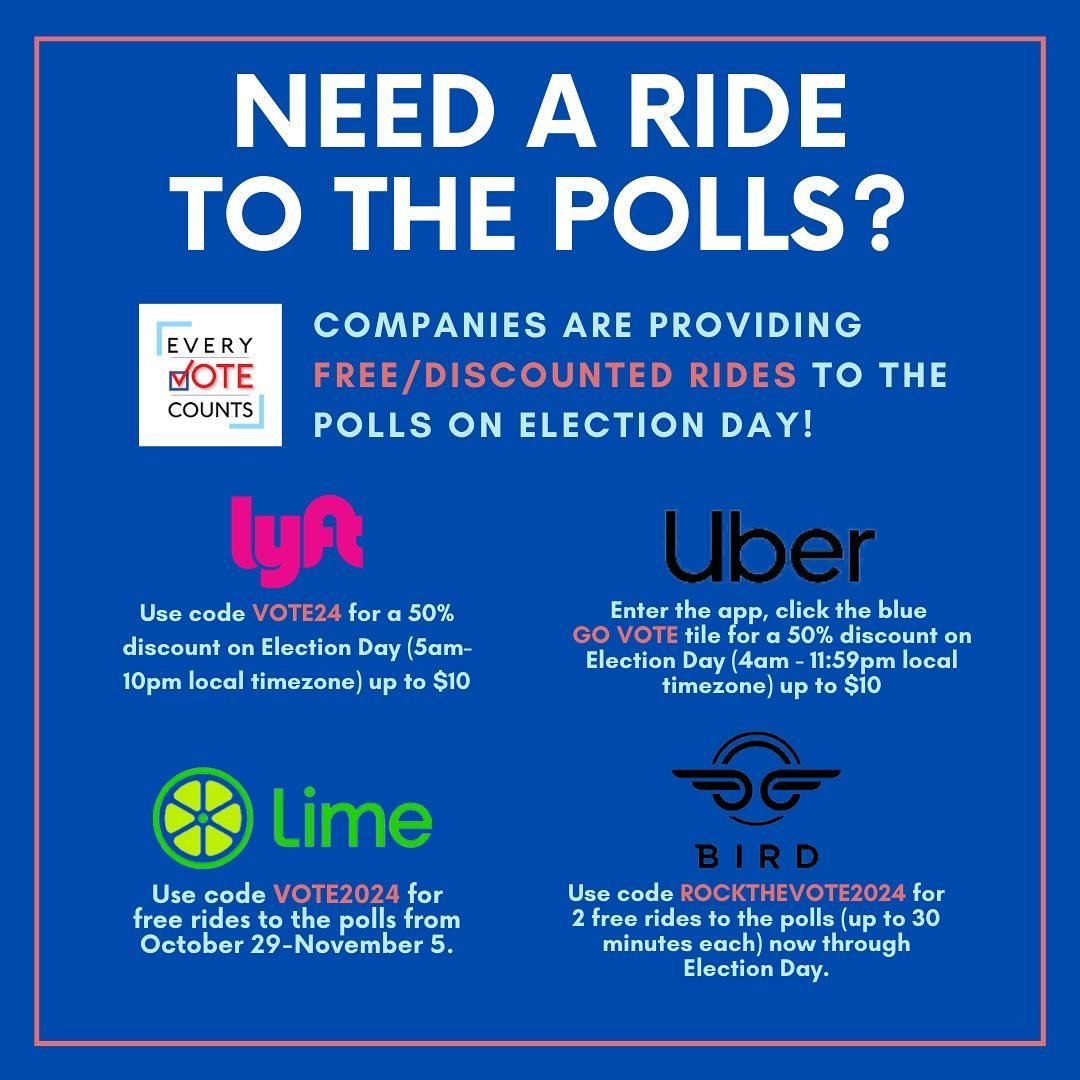

These restrictions and hurdles disproportionately affect minority voters, who are less likely to have flexible work schedules, and may find it difficult to afford or obtain a photo ID or reach nearby polling places.